By Monica E. Oss, Chief Executive Officer, OPEN MINDS

The latest numbers for the national 988 Suicide and Crisis Line are in. The hotline received over 16 million contacts during the 30 months from its July 2022 launch and the end of 2024, according to the recent reports, More Than 16 Million Crisis Line Calls Logged In First 30 Months Of 988 and Use Of The 988 Suicide And Crisis Lifeline At National, Regional, And State Levels. This includes contact with the Veterans Crisis Line, LGBTQ+ Line, and Native Line. Of all contacts, 70.1% were calls, 18.0% were texts, and 11.9% were chats.

In the 30-month period analyzed, the estimated lifetime 988 use prevalence was 2.4%. The national past-year 988 contact incidence rate was 23.7 per 1000 population, or a past-year 988 prevalence of 1.6%.

The study also revealed considerable state and regional differences in 988 usage. Regionally, the West had the highest past-year contact rate, at 27.1 per 1,000 residents and a prevalence of 1.8%. The South had the lowest use—20.0 per 1,000 and 1.3%, respectively. At the state level, Alaska and Vermont led the nation in 988 contact rates (45.3 and 40.2 per 1,000, respectively), whereas Delaware (12.5) and Alabama (14.4) recorded the lowest.

Since the 988 line went live, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has released guidelines with national standards for crisis systems. These guidelines are grounded in 11 principles emphasizing that crisis services must be comprehensive, coordinated, person-centered, equitable, trauma-informed, developmentally appropriate, recovery-oriented, safe, continuous (through follow-up care), and evidence-based.

We had a chance to hear about putting these crisis guidelines to best use in the OPEN MINDS Executive Roundtable, Strategies For Integrating SAMHSA’s National Behavioral Health Crisis Care Guidance: The Connections Health Solutions Case Study. Margie Balfour, M.D., Ph.D., Chief Clinical Quality Officer, and Chris Santarsiero, Vice President of Government Affairs, Connections Health Solutions (Connections), discussed the guidelines and how Connections Health Solutions played a central role in designing and operating the Southern Arizona Crisis Continuum, which has since become a nationally recognized model for crisis care.

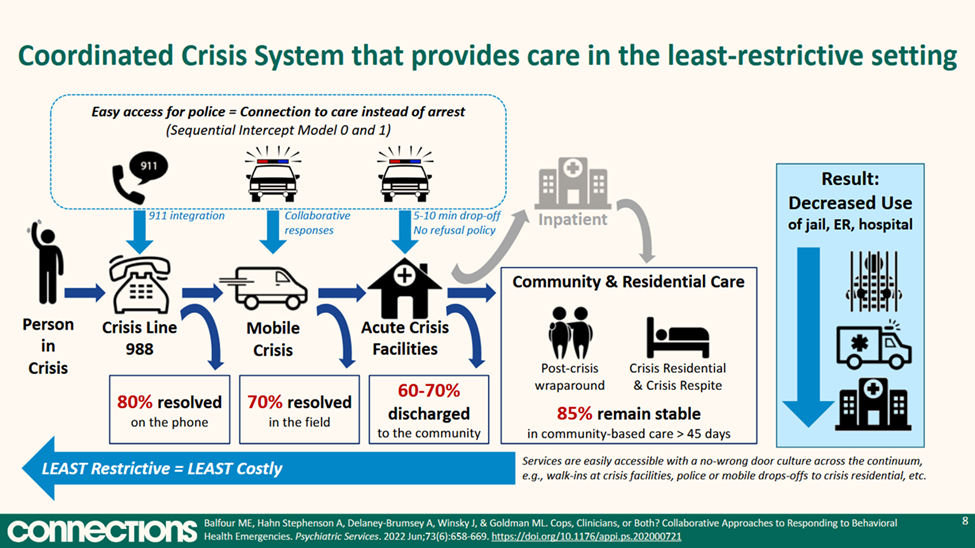

Arizona-based Connections is an immediate-access behavioral health crisis care provider organization with current locations in Arizona, Montana, Virginia, and Washington states—and locations coming in Oregon and Pennsylvania. Their model is tiered continuum of care that includes crisis calls over the telephone, mobile crisis teams (clinician-led or clinician-and-peer), and acute crisis facilities capable of handling involuntary, intoxicated, or highly agitated individuals. A distinguishing feature of the model is its emergency-room-like “no wrong door” policy, allowing law enforcement, emergency medical services (EMS), families, or individuals to drop off consumers at crisis centers without prior referral or eligibility screening.

The Connections team designed and operates the Southern Arizona Crisis Continuum. The services in Arizona were built using SAMHSA’s three pillars of crisis care—crisis hotlines, mobile crisis response, and high-acuity stabilization centers—and are organized along a continuum that ranges from least restrictive to most intensive. As part of the first pillar—crisis hotlines—upward of 90% of calls to the 988 crisis line are resolved over the telephone, and 988 call takers can directly schedule clinic appointments through shared software to support efficiency and prevent escalation.

In the second pillar—mobile crisis—there are 16 mobile crisis teams operating in Pima County, staffed by clinicians and peers (not law enforcement) who resolve 70% of cases in the field thanks to a strict one-hour response time. And finally, in the third pillar—high-acuity stabilization centers—all centers are low- or no-barrier, open 24/7, and never refuse individuals. These centers allow law enforcement to drop individuals off in under 10 minutes to support emergency room and jail avoidance and use trained clinical staff (not security guards) to deescalate situations.

Dr. Balfour and Mr. Santarsiero offered three pieces of strategic guidance for health and human service executives looking to adopt or expand crisis services—define services clearly and consistently, build a service line with a system in mind, and design for high-acuity and complex cases. With regard to the first issue, they noted that service definitions are crucial in replicating crisis services. Crisis stabilization service definitions varied wildly, even within the same state. Without definition, this lack of clarity makes planning, reimbursement, and outcomes tracking difficult.

Their second recommendation is to design new crisis services in the context of the overall system in the area—identifying gaps and mapping connections. Without a connected system of care that includes crisis lines, mobile response, and post-crisis support, the impact of a new crisis service will be limited. The context for new crisis service development should be to complement the current “system.”

Finally, they recommend designing all crisis services with the capacity to serve consumers with high acuity needs and consumers with complex support needs. The speakers noted that the most effective crisis systems operate with the same philosophy as emergency departments: no wrong door, no wrong consumer. To make this a reality, crisis services need to be designed with protocols and physical infrastructure that allow acceptance of drop-offs from police, EMS, mobile teams, and walk-ins, regardless of acuity. Additionally, access should be open to highly vulnerable individuals—including those without insurance, housing, or a support network. Some of the specific features of best practice crisis systems include staff trained in de-escalation without reliance on security guards, separate entrances for law enforcement, private de-escalation spaces, and peer-informed environments.

“When you’re creating these crisis systems, you want a high-resolution system where you’ve got both the high-acuity services and the services for lower-acuity patients,” said Dr. Balfour. “If you don’t have a specific level of care, patients will always default to the higher level of care. If you don’t have a crisis center, for example, they will default to an extended stabilization bed, and then after 23 hours of observation, they will go to the hospital. For lower acuity patients, that’s not a great experience. And the crisis system must be coordinated and moving smoothly with accountability and a single point of coordination. People will sometimes ask, do you really take everyone? What if they’re really high? These centers should be the highest level of care, so there are no exclusions for being too acute or too agitated. That’s our specialty. We want those people with us because they’re not going to get good care in the emergency room or jail.”

The demand for crisis services remains unmet—if you look at both the volume of 988 line traffic and the current overdose and suicide rates. To quote Dr. Balfour, “It’s not like you’re plopping down monopoly houses. Where you interface with the community must be tailored to local needs. Can you help bring people together so we can work on a better solution?”