By Monica E. Oss, Chief Executive Officer, OPEN MINDS

Loneliness is linked to an estimated 100 deaths every hour. In fact, nearly one in six people around the world experiences loneliness, according to the recent World Health Organization (WHO) report, From Loneliness To Social Connection: Charting A Path To Healthier Societies.

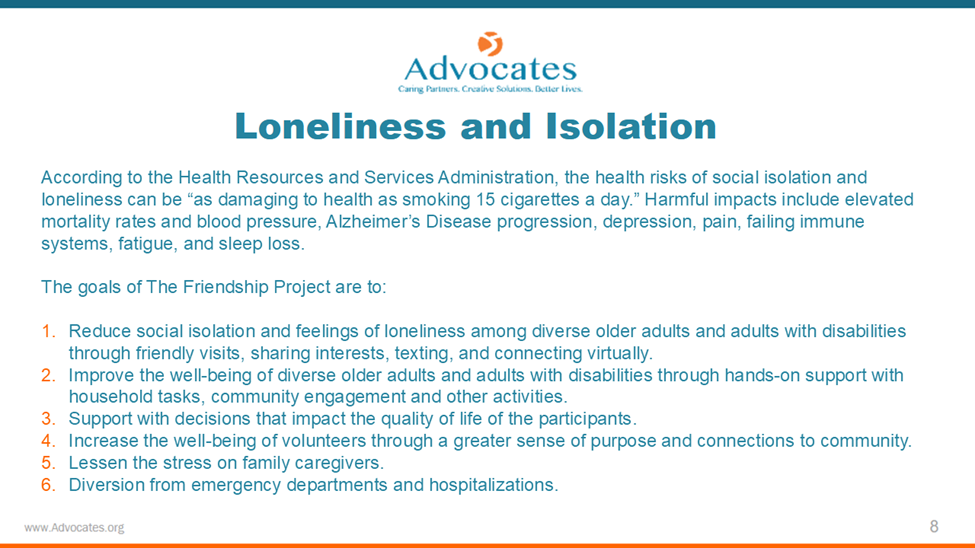

What is the connection? Loneliness contributes to increased risks of disease, early death, and poorer mental health. Loneliness is associated with a 14% higher risk of type 2 diabetes, a 29% increase in the risk of incident coronary heart disease, and a 32% increase in the risk of stroke. Loneliness can increase the risk of dementia by 25 to 50% and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease by 72%. And loneliness speeds the onset and increases the severity of mental health conditions, including depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, psychosis, post-traumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders.

For any health plan or provider organization executive, the new research puts loneliness at the top of the list of social conditions to address in order to improve consumer outcomes and reduce unnecessary health care spending. The question is what to do. We had a chance to hear from one organization that has made this investment in reducing loneliness and social isolation in the recent Executive Roundtable, Addressing Loneliness & Isolation In Individuals With I/DD & Mental Health Challenges: A Look At The Friendship Project From Advocates, featuring Jeff Keilson, Senior Vice President of Strategic Planning, and Pam McKillop, Director of Community Outreach Initiatives at Advocates.

Advocates, based in Massachusetts, is a $243 million non-profit organization that provides behavioral health, care management, and disability support services to individuals of all ages with disabilities and mental health challenges. It operates in locations throughout eastern and central Massachusetts, employs 2,500 staff, and serves more than 45,000 individuals and families annually.

Mr. Keilson and Ms. McKillop presented their program—the Friendship Project—which is designed to reduce isolation and enhance quality of life for adults with disabilities and mental health challenges. The program pairs participants with community volunteers to develop genuine, sustained friendships, and the pairs identify their preferences for connection, including community activities. The program hosts quarterly in-person group events for all participants and volunteers to strengthen ties in a safe way. The model began with funding from an Administration for Community Living grant through Community Care Corps and has an annual budget of $231,000. Additional funding was provided by a grant from the Massachusetts Attorney General, from the Massachusetts Department of Developmental Services, and from partner health plans. For consumers to participate, there is no charge.

The program has served 250 consumers—more than half with mental health conditions—through 205 volunteers over three and a half years. Formal outcome data is still being developed. But program participants report significant self-reported improvements in perceived quality of life, strengthened social networks, and reduced isolation and loneliness among consumers, family caregivers, and volunteers—as well as reductions in emergency room use and hospital visits.

Mr. Keilson and Ms. McKillop offered two pieces of advice to executives of organizations who are considering a program to address loneliness and foster consumers’ connections. First, find a unique and cost-effective approach that works for your organization and your communities. Second, build sustainability into this effort through multiple funding streams.

The speakers noted that creating the right program model is an important first step—a model that meets community needs while delivering cost-effective gains that health plans are willing to support. The Advocates team chose to leverage volunteers—a strategy that is both innovative and cost-effective. The annual program cost is $2,300 per person served. If you expand the circle of people involved in the program—the recipients, their caregivers, and staff—the program cost is under $1,000 per person engaged per year.

“From our perspective, the program is very low cost with great outcomes,” said Mr. Keilson. “It took me a year of advocacy to get funding from the state. Data helped, firsthand stories helped, and it certainly helped that we had some success. When you bring it down to the concrete successes and the stories, that makes it easier to obtain support.”

To overcome the initial risk of developing these programs, executives who leverage their early wins to build sustainability can seek multiple funding streams, including government grants, payer contracts, internal budget allocations, and community fundraising. Like any service line, initial success must be central to the case made to each potential funder.

“We began by looking for grant opportunities,” said Mr. Keilson. “There were many discussions then about how wise it would be to get a one-year grant and what would happen when the grant ends. We applied and got the ball rolling. We got the grant and began the program, and it was highly successful.”

When it comes to addressing the overlap between traditional health care services and the need for social supports, the Advocates team encouraged executives to not wait until “conditions are perfect.” This may mean running an initial pilot program that doesn’t have a long-term funding source but can still serve as the organization’s proof of concept, which can grow into a successful and sustainable service line that is part of a strategically managed service line portfolio.

Mr. Keilson said, “The need was so obvious and so tremendous in terms of people we support that we were willing to take the risk. We had a degree of confidence that if we were successful, we would be able to get ongoing funding that would sustain and grow the initiative.”