By Monica E. Oss, Chief Executive Officer, OPEN MINDS

A new study on autism treatment caught my eye. An analysis of complementary, alternative, and integrated medicines (CAIMs) approaches for treating autism found no evidence these treatments are effective.

The researchers evaluated 19 therapies for autism, including acupuncture, herbal medicine, animal-assisted therapy, music therapy, and vitamin D supplements, across 200 clinical trials. While some treatments did reach statistical significance in outcomes, the results were supported by little or weak evidence. Oxytocin treatment showed the highest levels of evidence, although the effects on core autism symptoms were not statistically significant. The researchers also cited safety concerns with many of the treatments, since fewer than half were assessed for side effects, tolerability, or other safety considerations. The analysis is meaningful at a very practical level since 90% of people with autism have tried at least one CAIM throughout their lives.

While the study focused on treatment of autism, it raises broader questions for the provider organization executive teams. One key question: What are the resources for managers of provider organizations to identify evidence-based practices (EBPs)? Where do managers find the “master lists” of best practices for services supporting consumers with substance use disorders (SUD), mental illnesses, autism, and more? But that question is just the start of many strategic issues, including how should managers select among the EBPs when designing programs?

My colleague, Stuart Buttlaire, Ph.D., OPEN MINDS vice president of clinical excellence and leadership, provided some interesting insights on these essential questions. He noted that, first, there is no one “master list” of EBPs for specialty provider organization executives to consult. In his experience, most executives rely on domain-specific authorities that use their own inclusion criteria, time frames, and methodological thresholds.

“Evidence-based” is not a simple yes-or-no label, Dr. Buttlaire said. “It reflects the strength and consistency of the published research, but it does not guarantee that a given intervention will work equally well in every clinic, for every population, or under every payer environment.”

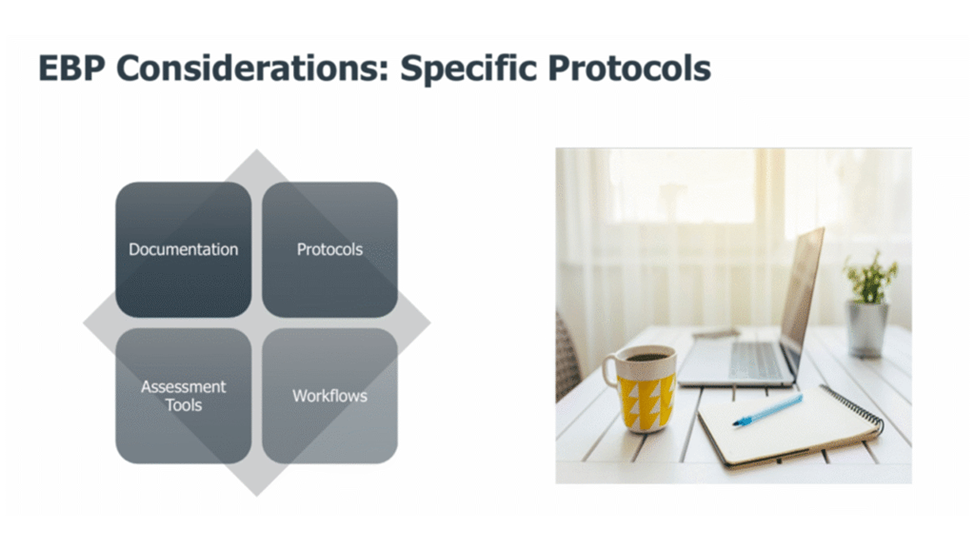

He outlined a four-pillar selection process for EBPs, emphasizing that leaders need to balance these four interdependent pillars:

- Population fit: age, acuity, comorbidities, and cultural or family context.

- Outcome priorities: symptom reduction, functional gains, caregiver burden, utilization, etc.

- Operational feasibility: workforce training, supervision demands, and the ability to score and sustain the model over time.

- Payment alignment: What payers will reimburse today and are likely to continue to support.

Dr. Buttlaire did caution that evidence and outcomes are not the same things. In his experience, they are often lumped together, but they are different levers in practice. For evidence-based practices, the question is, “Does this work under controlled conditions? Outcome measurement is more applied—is this working here, for our population, with our clinicians and families? This distinction matters from an executive standpoint. Evidence establishes credibility, while outcomes determine whether a program can be sustained over time. And outcomes are increasingly defined beyond symptom reduction to include functional gains, utilization outcomes (emergency department visits, hospitalization, residential placements), and total cost of care.

And then there is the payer issue. The question is what payers are willing to reimburse. And if payers are not willing to reimburse for particular practices, is the model one where consumers and their families are willing to pay privately? This creates a situation with two possible scenarios: a payer-reimbursed core aligned with EBPs and defensible outcomes and a privately financed (or not consistently covered) tier driven by family demand and perceived benefit.

From Dr. Buttlaire’s perspective, the risk for organizations isn’t simply choosing the “wrong” intervention, but a broader problem of misalignment. This includes building programs that are clinically thoughtful and well-intentioned but financially harder to sustain; relying on services that health plans initially tolerate but later narrow, restrict, or stop covering as they apply stricter evidence or medical necessity standards; and being unable to clearly explain what level of evidence supports a service and what outcomes they should reasonably expect.

“This EBP selection process is a practical way to protect programs, demonstrate value, and have more credible conversations with health plans when coverage or authorization criteria change,” said Dr. Buttlaire. “In this environment, outcomes measurement isn’t just a clinical exercise.”