By Monica E. Oss, Chief Executive Officer, OPEN MINDS

The path for addressing homelessness and housing insecurity appears to be on a new trajectory. An executive order issued last month shifts federal policy on homelessness and housing policy toward involuntary civil commitment. And last Sunday, August 10, in a social media post, President Trump wrote, “The Homeless have to move out, IMMEDIATELY…We will give you places to stay, but FAR from the Capital”.

And earlier this year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) signaled plans to reduce reimbursement for health-related social needs, including housing. The agency rescinded previous guidance regarding coverage of services and supports.

The link between homelessness and health care utilization is well documented. In one of many analyses, in Maricopa County, Arizona, individuals with serious mental illness (SMI) who were also chronically homeless had overall average annual costs of $54,978—significantly more than the corresponding $37,402 for individuals in supported housing. People in supported housing also showed lower inpatient costs per person per year, at $11,992, compared with $17,778 for the chronically homeless.

And a new study—Health Care Access And Use Among Adults Experiencing Homelessness—adds some additional perspectives. Of homeless individuals in California, 38.6% used the emergency department (ED), and 21.8% had an overnight hospitalization during the previous six months. The use of these levels of care was roughly the same for sheltered and unsheltered individuals. Not surprisingly, 39.1% reported no ambulatory care use during the previous year, 24.3% reported an unmet health care need, and 23.3% reported an unmet medication need during the previous 6 months.

We got a deep dive into the best practices of working with homeless populations in a recent session, Housing As Health Care—Addressing The Housing & Homelessness Crisis With ACMH, Inc., during The 2025 OPEN MINDS Strategy & Innovation Institute. The session was led by Daniel Johansson, Chief Executive Officer of ACMH, Inc.

Based in New York City, ACMH provides transitional housing programs with a rehabilitative focus, permanent housing with direct service supports for consumers with chronic mental health and substance use disorders (SUD), and care management for adults with mental illness and other chronic medical conditions. The $47.1 million organization has a staff of 355 people serving the boroughs of Manhattan, Queens, and the Bronx.

ACMH took a number of steps to transform its operations to treat housing as a foundational component of health care. This included developing a continuum of services, from transitional community residences and permanent supportive housing to scattered-site apartments and innovative, low-barrier housing. In addition, ACMH has established a crisis respite program; launched a Safe Option Support (SOS) team for street-level engagement; and implemented an anti-racism plan for both service delivery and workforce development.

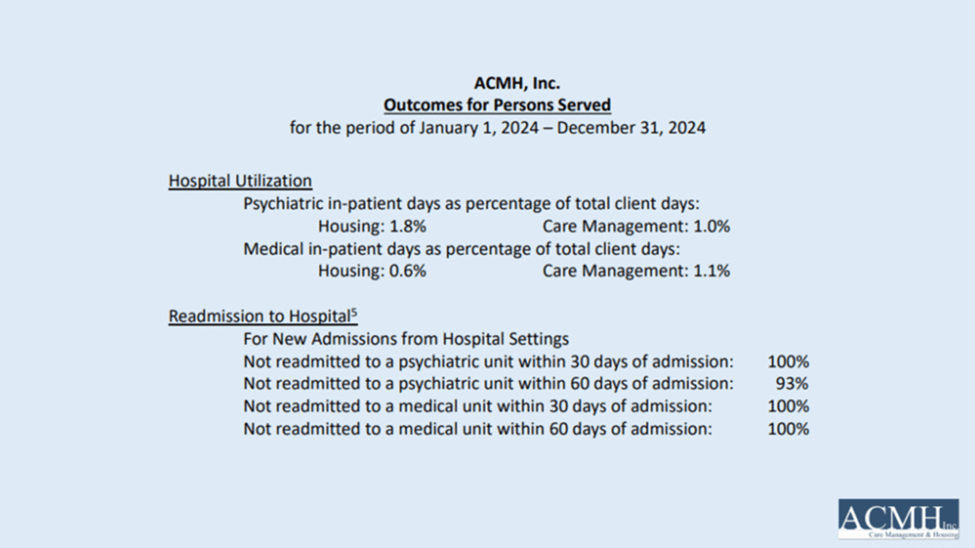

The ACMH team has invested in a performance measurement system to assess the impact of their housing initiatives on health care utilization. For clients with ACMH supported housing, inpatient days were less than 1% of total days. And for those admitted, their 30-day admission rate was 0%—and their 60-day readmission rate was 7%.

And 60% of ACMH consumers were ‘consistently’ adherent to prescribed medications—varying from 60% in housing programs to 25% supported by an ACT team. And 75% of consumers served were not re-arrested.

For other executives considering providing service to address the needs of the homeless population, Mr. Johansson has some advice from his long experience in this market space. This advice includes anticipating funding volatility, investing in data and cultural competence, and forming partnerships—both politically and in the community—for success.

The funding issue is a big one. Mr. Johansson said that executives must be prepared to combine fragmented funding sources to successfully support housing-insecure consumers. ACMH pursues multiple reimbursement pathways—including fee-for-service, managed care, and grant funding—to ensure program continuity and scalability. He advises organizations to align services with Medicaid’s goals for cost containment, especially around reducing ED use and inpatient stays. And in the face of federal rollbacks, ACMH has built a funding structure that doesn’t rely solely on waivers.

“States are going to be looking to save those Medicaid dollars more than ever, and that’s our space to be innovative,” he said. “Just don’t wait for ideal funding; get started with what’s available and evolve. We just took advantage of not knowing how we would be able to continue to fund crisis respite. Our respite program is licensed now by the State Office of Mental Health. It’s an eligible service for reimbursement, both in Medicaid fee-for-service and in managed care.”

Beyond having a braided funding approach to revenue, Mr. Johansson emphasized the importance of building an organizational culture that acts on data to support these consumers. ACMH tracks outcomes like hospitalization rates, medication adherence, and equity indicators. It also uses data to address the sensitivity of consumers’ cultural needs.

Culture is everything in human services,” he noted. “We track inpatient days, medication adherence, linkage to primary care, and prison recidivism, but we also ask consumers whether they have access to culturally appropriate and language-appropriate services. Our vision is to create an intentional culture of anti-racism that promotes actionable change at individual, interpersonal, and institutional levels.”