By Monica E. Oss, Chief Executive Officer, OPEN MINDS

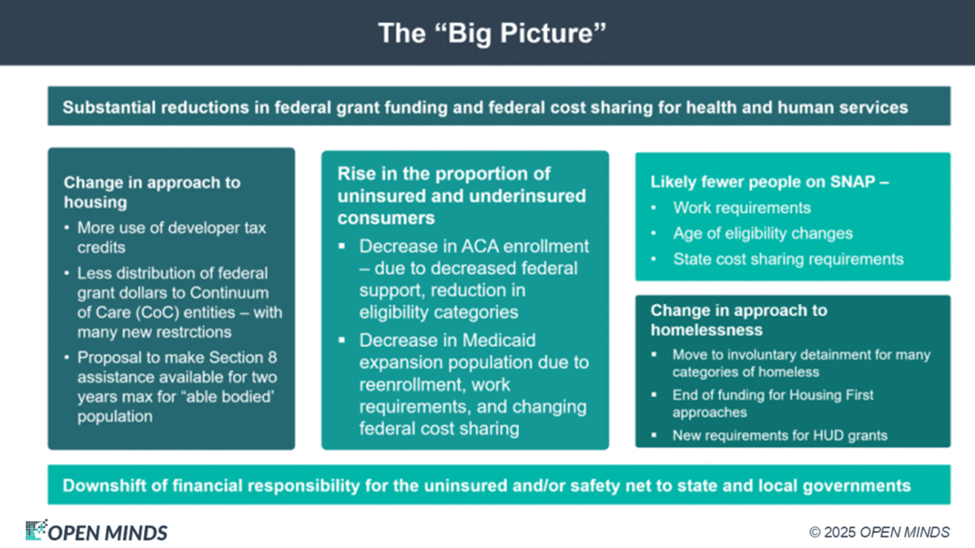

The past year’s many shifts in federal health and human service policies have brought a host of “trickle down” effects to the field. Some of these changes affect reimbursement of specific services—like the plan to discontinue Medicaid reimbursement for health-related social needs and new criteria for services for the homeless and housing support grants.

Several of the changes affect state budgets directly. State-directed Medicaid payments will be lowered to a Medicare-equivalent ceiling rate. States will be prohibited from creating new provider taxes to fund Medicaid. And states will now need to pay part of the cost of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits.

This is happening at the same time that the last Congressional budget bill laid out plans for an estimated $1 trillion less in federal Medicaid spending over 10 years (15% reduction from current spending)—with a higher proportion of costs to be borne by state and local governments. For Medicare, the bill included an estimated $500 billion in cuts to Medicare spending between 2026 and 2034.

And there will likely be a rise in the number of people without insurance in the next year—an estimated additional 10 to 16 million more uninsured persons. This is due to the end of the tax support for premiums expiring for ACA/Exchange plan members, new pre-enrollment verification processes with new documentation requirements for ACA/Exchange plan members, Medicaid expansion work requirements for individuals ages 19 to 64, and new six-month eligibility redetermination requirements for Medicaid.

The cumulative effect of these developments will change the role of county government in health and human services in 2026. With more limited federal and state spending—and more unfunded mandates for health care, housing, and nutrition—the county role as the payer of last resort and the locus for braiding health and human funding will be magnified.

The evolving role of county government and emerging county management best practices was the focus of a recent Executive Roundtable, The Evolving Role Of Counties In Oversight & Service Delivery In Behavioral Health, led by my colleagues, OPEN MINDS Senior Advisors Margaret Mays, Ph.D., Sharon Hicks, and Michael Allen. They discussed the growing pressure on counties to serve the rising needs of their communities with increasingly limited resources—to serve as “local accountability hubs”—that is driving new county delivery and contracting models.

The speakers discussed the specifics of how the county role is evolving. Many counties are responsible for behavioral health services for the uninsured populations, 988 crisis response coordination, child welfare and juvenile justice, support services for the aging and disabled populations, services for the forensic population, and more. County health and human service agencies are often responsible for waiver management, service coordination, maintaining state and federal grant funding, and coordination with school services, employment agencies, and housing initiatives.

With these many added responsibilities, along with the expiration of COVID-era and American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 funds, managers in county agencies are rethinking how they finance and contract for services. This includes considering service models that incorporate more performance-based contracting and use value-based reimbursement models.

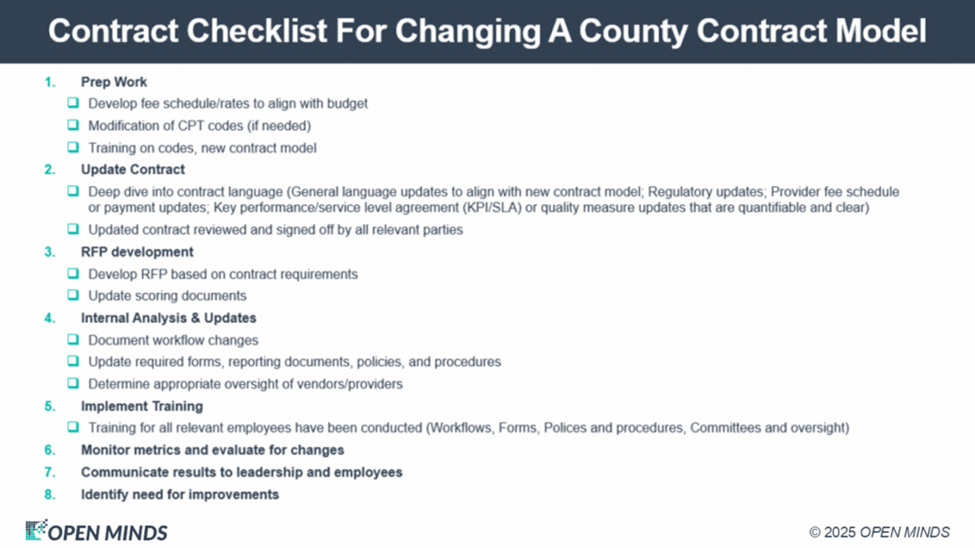

To illustrate this phenomenon, the team described their current work with a county to do just that. This county agency historically used a cost-based reimbursement model to fund behavioral health services—a structure that was stable but limited in transparency and performance accountability. The county executives’ goal was to move to some form of performance-based contracting model. To do this, the county embarked on a staged transition—from cost-based to fee-for-service (FFS) to VBR. This transition model would allow the county to introduce standardized coding, utilization visibility, and clearer performance expectations to their contracted provider organizations.

To facilitate the transition process, the OPEN MINDS team reviewed the county’s current contracts for behavioral health services, the associated costs, and the effective rates. Based on that information, the team developed initial FFS rates using current procedural terminology (CPT) coding. The team also developed and delivered technical assistance in CPT code translation, CPT coding training, and FFS management best practices training. The new rate model was incorporated into the county’s existing processes for governance, oversight, readiness reviews, and due diligence.

As a result, the county successfully transitioned to FFS late in 2025. The county managers are in the process of streamlining administrative and operating processes. The timeline for transition to performance-based contracting models has not been set.

“The most important component in any kind of contract change, regardless of whether you’re asked to go for pay for performance or some kind of case rate, is to first understand who the stakeholder in charge is,” said Ms. Hicks. “This helps to understand all the consequences, some unintended, and to make sure you have the data infrastructure to support the new model. Sometimes, the contract itself will require new work that you didn’t consider as you were building your new model. It’s important to do that deep dive into your current contract and then be able to compare that to your new contract.”

For provider organization strategy, shifting pressure on counties is both a threat and an opportunity. The threat is that counties will try to continue the “trickle down” from the federal and state governments, passing along more responsibilities for lower reimbursement. Provider organization executive teams need to know the cost of their county contracts and be prepared to say “no” to financially untenable contracts.

At the same time, this is an opportunity for entrepreneurial provider organizations to develop “alternative” service models to meet the needs of county government and their citizens. Many forward-looking county executives are redesigning their service delivery systems for behavioral health, child welfare, senior services, housing, and more. Provider organization viability will depend on understanding how counties interpret Medicaid rules, enforce licensure and documentation standards, and structure oversight, even when counties are not the direct payer.

Provider organization executive teams interested in continuing and/or expanding their revenue from counties need a “county strategy” that includes an understanding of how uninsured and underinsured populations are served and service line planning with an understanding of the investments needed to support new services.

Health and human service executives face many different challenges depending on the markets they operate in, but a common strategic question should be, how do they stay viable and competitive as counties redesign oversight and contracting models. Finding the “right” answer will be critical, but according to Mr. Allen, success will only be found through steady adaptation and improvement. He noted, “With any large change, perfection is not the goal. The goal is to get started and then iterate while seeking continuous improvement. You get a plan, you communicate, and then you work on it. Don’t get paralyzed by the idea of perfection. You’re not going to start out with a perfect contract.”