By Monica E. Oss, Chief Executive Officer, OPEN MINDS

In the recent OPEN MINDS briefing, Whose Evidence?, my colleague, Stuart Buttlaire, Ph.D., OPEN MINDS vice president of clinical excellence and leadership, discussed the realities of navigating the question of evidence-based practices (EBPs). The bottom line—there is no one-size-fits-all solution to selecting EBPs and designing clinical services.

I asked Rick Gutierrez, Ph.D., OPEN MINDS senior advisor, to expand on the issue specific to the treatment of autism and disability-related services. The questions—what is the current thinking about “best practices?” What are current payer policies related to those practices? He noted that there is no “singular” source of EBPs for autism. Most executive teams will look to the professional disciplines and organizations for guidance. “The Council of Autism Service Providers is a great resource to helping improve the quality of care that is provided,” Dr. Gutierrez said.

From his vantage point, the selection of EBP for autism is happening at the state level—most states have created regulations that outline what is considered an EBP for autism treatment. Those often include applied behavior analysis (ABA), occupational therapy, physical therapy, and speech therapy. For evaluating individuals for autism, the standard is the ADOS (Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule), along with clinical checklists, screening tools, observation, interviews, and record reviews.

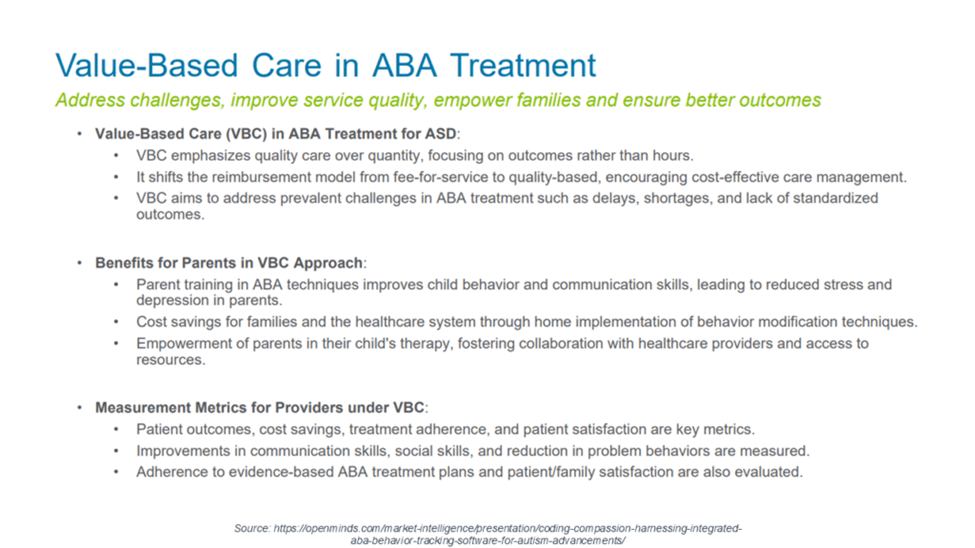

And while all states now mandate insurance coverage for autism services, Dr. Gutierrez observed that there are growing concerns about treatment costs. A working group in Indiana has recommended a lifetime cap of 4,000 hours of ABA therapy, then 15 hours of targeted therapy per week. In 2025, Nebraska slashed Medicaid reimbursement for ABA by as much as nearly 50%. This is creating an uncomfortable intersection of science and policy.

Dr. Gutierrez also brought up the issue of EBPs for disorders that co-occur with autism, adding that “I don’t think we have done a great job of establishing how to make some of the EBPs more accessible to someone with autism or I/DD … Since the pandemic, we have seen an uptick of individuals presenting with autism/developmental disability and a co-occurring mental health conditions. Unfortunately, there are not many mental health clinicians trained to work with people with I/DD or autism. The population often struggles with diagnostic overshadowing, where medical and psychological concerns are attributed to autism instead of investigating other conditions such as anxiety, depression, or trauma.”

But his observation is that workforce limitations remain a major barrier. “ABA or disability provider organizations and their teams, generally speaking, are not trained to evaluate or address mental health conditions, let alone understand the medications that are prescribed to address some of these conditions. It really requires the clinician to operate at the top of their license and remain within the scope of practice and coordinate care as needed.”

Dr. Gutierrez cautioned state policymakers that short-term limits on autism treatment may cost state Medicaid plans more in the long run because they will have to pay more for long-term care and supports. “They still must ensure people meet their treatment goals and receive high-quality care.”