By Monica E. Oss, Chief Executive Officer, OPEN MINDS

I’ve long viewed the medical loss ratio (MLR) requirements established under the Affordable Care Act as an important consumer protection. By requiring health plans to spend a defined share of premium revenue on medical care—80% in the individual and small group markets and 85% in the large group market—the policy was intended to constrain excessive administrative costs and profits while improving value for consumers.

A recent analysis, The Unintended Consequences Of The ACA’s Medical Loss Ratio Requirement, takes aim at the MLR regulations. The authors concluded that “there is little evidence that the MLR requirement has promoted premium affordability or constrained insurer profits as intended; instead, the MLR drives higher premiums and higher medical care spending and presents other unintended consequences that warrant attention.”

Whether one agrees with those conclusions or not, the article is most compelling in its examination of how the MLR has shaped health plan behavior—particularly by influencing both horizontal and vertical integration strategies.

On the horizontal integration front, the authors posit that large, national insurers with broad enrollment across multiple markets are better positioned to spread administrative costs across a larger premium base and multiple lines of business. This creates a structural advantage relative to smaller or regional plans with fewer members and less diversification. Notably, this outcome aligns with one of the original assumptions behind the ACA’s managed competition model: that scale would promote administrative efficiency. The extent to which those efficiencies have translated into lower premiums for consumers, however, remains open to debate.

The authors also attribute the growth of vertical integration in health care to incentives created by the MLR framework. Health plan ownership of hospitals, physician groups, pharmacies, and pharmacy benefit managers allows internal payments to wholly owned subsidiaries to be counted as medical spending for MLR purposes—at times with reimbursement rates higher than other provider organizations. According to the authors, these internal pricing arrangements can raise reported MLRs while profits are retained within the broader corporate structure.

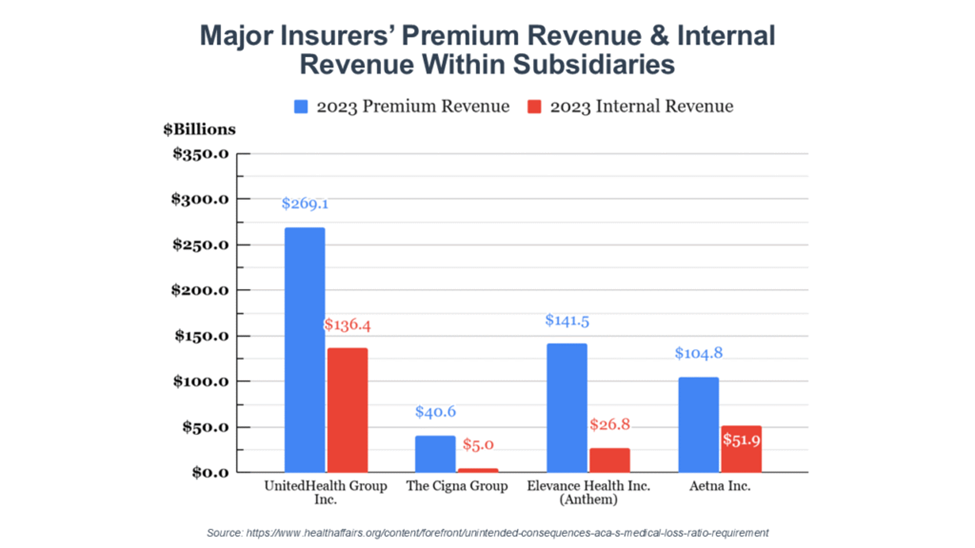

To illustrate this dynamic, the authors point to differences between premium revenue and subsidiary revenue across major insurers. In the data presented, subsidiary revenue represents approximately 12.4% of premium revenue for Cigna, 19% for Elevance Health, 49.5% for Aetna, and 50.7% for UnitedHealth Group. The authors argue that these figures underscore how vertically integrated business models may interact with MLR accounting in ways that differ substantially from plans that rely primarily on independent provider networks.

The policy question raised by the authors is not simply whether the MLR has succeeded or failed, but whether it remains the most effective primary regulatory tool in an increasingly consolidated and vertically integrated market. They suggest several potential refinements, including targeted MLR relief—such as reduced thresholds or time-limited suspensions—for small or new market entrants, redirecting MLR rebates to state reinsurance programs to lower future premiums, and stronger enforcement of existing price transparency requirements and the No Surprises Act.

My colleague, Stuart Buttlaire, Ph.D., OPEN MINDS vice president of clinical excellence and leadership, commented, “I agree with the authors that the medical loss ratio has functioned as a market-shaping mechanism, not just a consumer protection rule, and that it has likely accelerated both horizontal and vertical integration. Where I’m less convinced is the implied causal leap from MLR to higher premiums or excessive medical spending. Those trends were already underway due to provider consolidation, specialty drug costs, and benefit expansion. To me, the more important insight isn’t whether MLR ‘worked’ or ‘failed,’ but that it creates predictable incentives—and health plans, unsurprisingly, adapt to them. The policy question isn’t whether to abandon MLR, but whether it’s still the right primary tool given how sophisticated and vertically integrated the market has become.”

Paul M. Duck, OPEN MINDS chief strategy officer, had a similar take on the analysis. “I agree that MLR has created strong incentives around scale and has likely accelerated both horizontal and vertical integration, but I’m less convinced that MLR itself is a meaningful driver of higher premiums. In my view, premium growth is still far more directly tied to underlying provider costs, benefit mandates, and broader market cost dynamics, with MLR functioning more as an accounting constraint than a true cost-control lever. That said, I do think the authors raise an important policy question: not whether MLR should go away, but

As health care cost pressures continue to mount, policy approaches to population health management—including MLR oversight, care coordination requirements, and benefit mandates—are likely to evolve. How these changes play out will have meaningful implications for access, network design, and reimbursement, particularly for individuals with behavioral health and cognitive conditions.