By Monica E. Oss, Chief Executive Officer, OPEN MINDS

It has been almost 30 years since the original Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study—Relationship Of Childhood Abuse And Household Dysfunction To Many Of The Leading Causes Of Death In Adults—was conducted at Kaiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997. The findings were compelling. Persons who had experienced four or more ‘adverse experiences’ as children had 4- to 12-fold increased health risks for alcoholism, drug abuse, depression, and suicide attempts as adults. Adverse childhood exposures also had a relationship to the presence of ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, skeletal fractures, and liver disease. While the research was—and is—compelling, health care policy and practice is spotty in terms of embracing the findings.

A new study—Adverse Childhood Experiences And Chronic Health Outcomes: Evidence From 33 US States In The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2019-2023—confirmed the original findings and provides interesting insights for designing health care services for children. Using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an analysis found 24.4% of adults reported three or more ACE exposures (considered ‘high’), using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Emotional abuse (35%), parental separation (30.9%), and substance abuse by household members (27.4%) were the most reported ACEs.

Individuals with high ACE exposure had higher risks of depression, smoking, coronary heart disease, and other conditions. Adults with three or more ACEs were three times as likely to report depressive disorder, twice as likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and 1.6 times as likely to have coronary heart disease. In addition, people with races/ethnicities other than white had higher risk ratios for these conditions.

Geographically, ACE prevalence and health-related outcomes varied by state, with Oregon and Nevada exhibiting the highest mean ACE scores—between 2.5 and 3. North Dakota and Mississippi had the lowest mean scores, between 1.1 and 1.5.

The question for health plan managers is what to do with these findings—how to prevent ACEs from occurring and how to address the result of ACE exposure. We heard recently how one health plan and one provider organization launched an initiative to address this issue at The 2025 OPEN MINDS Service Excellence Institute, in the session, Advances In Early Intervention Service Models For Children & Families. Ryan Estes, Chief Operating Officer at Coastal Horizons Center (Coastal Horizons), and Michael Smith, M.D., Chief Medical Officer at Trillium Health Resources (Trillium), discussed the principles, application, and outcomes of their Child First model of early intervention services.

Trillium is a Medicaid managed care organization with a total operating revenue of $742 million and 2,000 employees who manage care for over 80,000 consumers across 46 North Carolina counties. Coastal Horizons is a private non-profit provider organization with $62.6 million in annual revenue and 700 employees, providing mental health, substance use, crisis, and justice-related services for over 20,000 consumers each year in 58 North Carolina counties.

To reduce adverse experiences among children, Coastal Horizons and Trillium implemented an outreach program based on the evidence-based Child First model, out of Yale University. This initiative started in 2014.

The model uses a two-generation intervention to work with parents and children together in their homes, to connect them with the services they need to support healthy child development. Clinical services include comprehensive assessments, a child and family plan of care, mental health classroom consultation, pediatric care, primary care, substance abuse treatment, and child-parent psychotherapy. Community support services can include pediatric care, primary care, special education, parenting groups, substance abuse treatment, legal assistance, domestic violence services, housing, job training, computer training, clothing and furniture, transportation, food stamps/Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, adult education, and connections to public assistance. The top three diagnoses of children referred into the program are severe stress, oppositional defiant disorder, and parent-biological child conflict.

Dr. Smith explained the rationale for the model: “Foundational skills can be interrupted by trauma. And disruptions of those foundational skills can last into adulthood…When the stress gets overwhelming, those stress hormones can damage brain structures, which can lead to the development of depression, anxiety, other mental illnesses, and dysregulation of emotions, which can lead to risky behaviors, self-injury, substance abuse, disorders, personality disorders, right on down the line….There can be a link to that early childhood trauma for a lot of the diseases, the illnesses that we see in adults. And it’s not just mental health illnesses. Studies that show a link to physical illnesses, a susceptibility to being more physically ill.”

Reimbursement for these services is through both fee-for-service and per diem rates. The fee-for-service model is paid under Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. There is also a per diem under an “in lieu of” service definition to cover clinical services, travel, and case management.

The speakers offered a couple of recommendations for executives looking to replicate early intervention models like Child First. These include an organizational commitment to evidence-based practice and the ability to leverage partnerships.

First and foremost, launching an evidence-based service line—such as Child First—demands both processes and training to assure model fidelity. Training through the Child First Learning Collaborative includes 4 on-site intensive sessions (10+ days) over 12 months, a distance learning curriculum, a Child-Parent Psychotherapy Learning Collaborative with 3 on-site sessions (8 days) over 12 months, and specialty conferences targeted to the needs of the regions served. Reflective clinical consultation provided by a Child First Regional Clinical Director, which can be on-site or web-based, includes 12 months of weekly to biweekly clinical consultation, ongoing biweekly clinical supervision, and network meetings. “This is an expensive model,” said Mr. Estes. “I will also say you are getting your money’s worth when you implement this, but there is money in the licensing fees, the electronic health record, the training, all aspects of consultation, the aspects of the model that must be taught, as well as the child, parent, and psychotherapy learning. Those are different aspects of highly intensive training. I would say, as you’re selecting a clinician, you want someone who’s hungry to learn.”

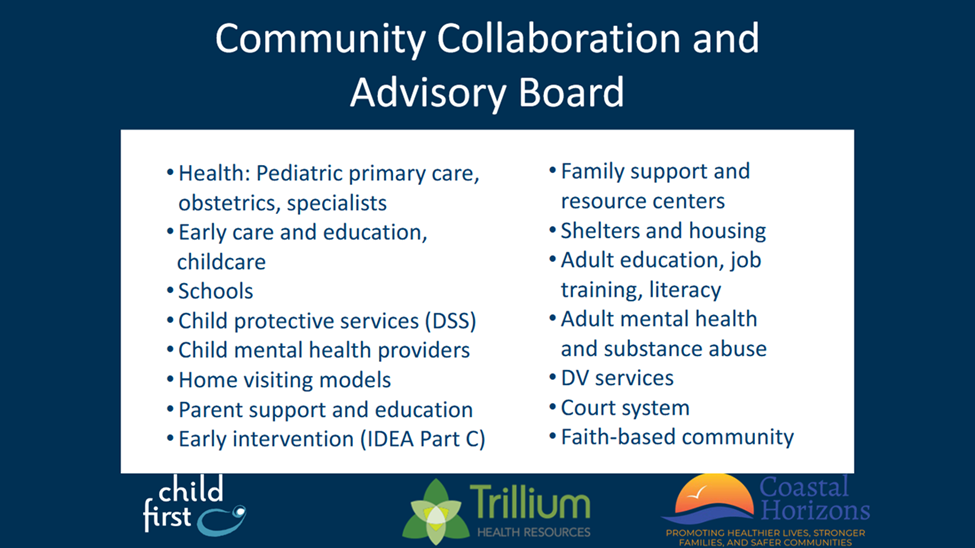

And provider organizations must have the ability to build cross-system partnerships. The Child First model depends on community advisory boards—including pediatricians, educators, Disability Support Services, and domestic violence services—to sustain collaboration and reduce duplication.

“This is not a model where you’re the provider,” said Mr. Estes. “It’s the community. We developed a community collaborative prior to implementing it. We have social services at the table. We have other mental health service providers, early intervention, and the school systems. So, it’s the health care system. If you were to implement this, who would be those community partners that are helping you to develop out your work?”

The question for health plan executives is whether to invest in a prevention model like this one. Mr. Estes noted, “If you’re a payer, you’re probably already serving these kids, and they are getting other services, whether intensive at-home or day treatment programs, but they’re not being served most effectively. And, under this model, the parent and the child are getting better—two for the price of one.” Dr. Smith added, “What we want to see in these kids is a healing of the trauma, a healing of the damage, to help them move forward with their lives. This model does make a difference.”